Jack Scates

The counter-extremism organisation Hope Not Hate (HnH) recently warned that children are increasingly at risk of right-wing extremist radicalisation. Right-wing extremism (RWE) includes forms that see violence as legitimate in fighting a ‘political and ethnic “enemy” (individuals with different culture, religion, nationality or sexual orientation) seen as a threat.’ As part of this process, radicalisation ‘leads a person to hold extremist beliefs’, which could lead to political violence or even terrorism.

In 2017-18, 682 children were referred to the UK’s counter-terrorism programme “Channel” over RWE concerns – a stark rise from 131 in 2014-15. Some were plotting terrorist attacks; 10 out of the 12 under-18s arrested for terrorism offences in the UK during 2019 were linked to RWE. For example, Harry Vaughn was an 18 year-old with four A* A-level grades as well as a neo-Nazi terrorist, who admitted to fourteen terrorism offences and two child abuse image offences in 2020, after being caught with bomb-making instructions. Head of London Metropolitan Counter-terrorism Policing Richard Smith said the case shows how ‘any young person [can] be susceptible to radicalisation.’

Yet Vaughan is not the most surprising case. That dubious title goes to the former UK leader of the extreme neo-Nazi group Feuerkrieg Division (FKD). Their ascent to fame came in 2020 due to their online calls for terrorism at the behest of their leader, the “Commander.” The group members were unaware that this “Commander” was a 13 year old boy in Estonia. Also 13 at the time he started offending was the UK leader for the FKD, who on 8 February 2021 became the youngest British citizen sentenced for terrorism charges. He owed his leadership position to online right-wing extremist activity, meaning children can rise through the ranks because they are judged on their extremist mindset, not age.

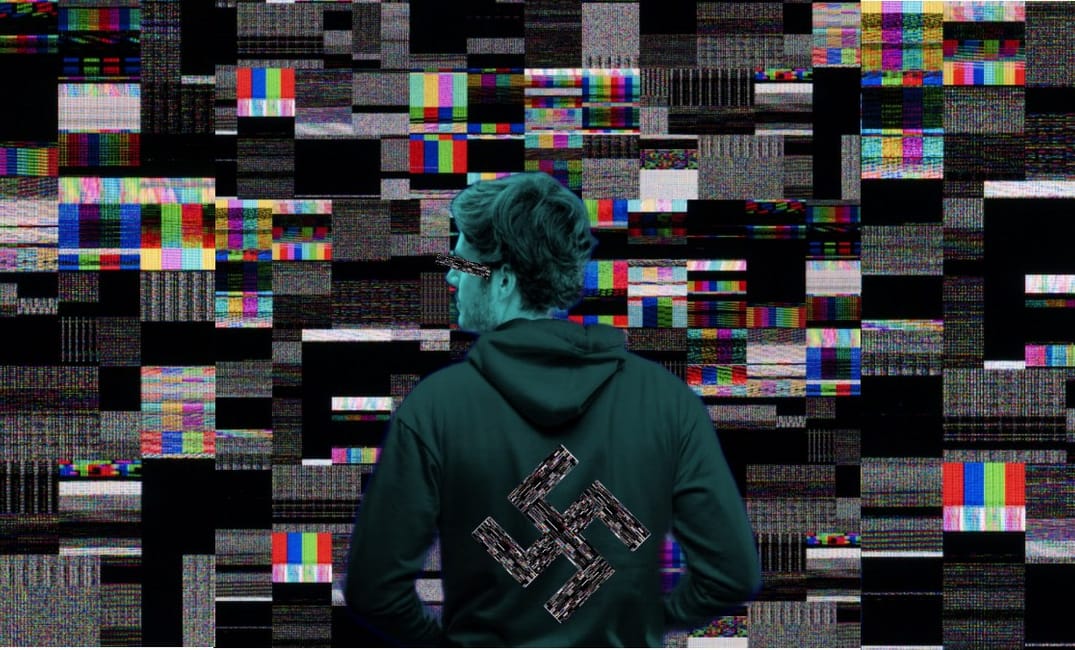

This online shift is growing; the head of counter-extremism charity Exit UK Nigel Bromage believes that 70% of radicalised individuals helped by his organisation were recruited online. This phenomenon has led to further child radicalisation, with the head of UK Counter-terrorism policing, Neil Basu warning that the COVID-19 pandemic has left young people spending more time online away from ‘protective influences,’ increasing the risk of radicalisation.

Why do far-right extremists aim to groom and radicalise children?

RWE expert Professor Cynthia Miller-Idriss contends that young people can feel “let down by the adult world”, with RWE involvement forming a kind of “resistance.” Undoubtedly, children are more vulnerable to extremist propaganda. For example, SALTO-YOUTH an EU organisation supporting youth education confirmed that children are particularly vulnerable to radicalisation for reasons when searching for a “sense of identity.” Recent cases have included teenagers suffering from “social disorder[s]”, suggesting their involvement in extremism is affected by feelings of “isolation and social awkwardness.” However, this cannot be separated from the fact that right-wing extremists seek them out to be groomed and exploited.

HnH expert Patrick Hermansson asserts that right-wing extremists recruit children because they view them as “the future of their movement[s].” Exemplifying this trend is Patriotic Alternative, a British white supremacist organisation, which recruits children as part of an effort to promote their “political outlook” to the next generation and undermine what they call the “left-wing liberal establishment educational system.”

Certain right-wing extremist and terrorist groups circulate texts encouraging child recruitment. The Atomwaffen Division (international neo-Nazi terrorist group) bases its ideology around the writings of neo-Nazi James Mason entitled Siege, which instructs them to recruit individuals “while they are YOUNG.” Further down this neo-Nazi rabbit hole, young people with an interest in what is called “esoteric Nazism” can be left vulnerable to child sexual exploitation (CSE). Some right-wing extremists like the UK-based Nazi-Satanist terrorist group Order of the Nine Angels incorporate CSE into their ideology. One member called Ryan Fleming, who was also a regional organiser of the neo-Nazi National Action terrorist group (banned in 2016 by UK authorities), was jailed in 2017 for sexually abusing a 14-year-old. The danger of groups containing members like Fleming contacting minors is as obvious as it is terrifying.

What methods do right-wing extremists use to recruit children?

Right-wing extremists typically utilise social media to recruit children. CARR fellow Cristina Ariza notes that white supremacist groups use livestreams targeting teenagers on YouTube. Their recruitment activities also take place on less mainstream social media websites like Telegram, which is lightly moderated and anonymous, making it a favourite for right-wing extremist recruiters.

These recruiters use “offensive humour” to disguise extremist rhetoric and draw individuals in, before exposing them to more extreme materials. Moderators of right-wing extremist chats encourage new members to post a “racist meme” to ensure they are ‘genuine.’ This is described as “lulz” or an ironic form of “edgy humour”, but research illustrates how this can lead to people considering extremist positions, preparing them for future radicalisation towards violence.

More specifically for children, right-wing extremists use “video games” to begin the radicalisation process. Nigel Bromage has highlighted the use of ‘neo-Nazi video games”, that encourage violence against ‘ethnic communities [and] different religions.” In one case, a 9-year-old boy had been radicalised by his older brother, who began using these video games, which illustrates how certain pieces of RWE propaganda target children.

Once children are drawn into extremism, they often receive a “warm welcome” from older activists, and are presented with extremist “role models” like the neo-Nazi members of National Action. Children enter a “filter bubble”; where they overwhelmingly interact with like-minded extremists – without encountering competing views – thus speeding up radicalisation. From this point of view children, radicalised by adults, are the victims of grooming.

Yet children have also become involved in the recruitment of their peers. The FKD was one example; another is the 15 year-old leader of the extreme-right pro-terror group called The British Hand, who encourage attacks on immigrants whilst providing instruction for manufacturing weapons. Even adult-led extremist groups use children to recruit people their own age – Patriotic Alternative live stream channels host “Zoomer Night” episodes aimed at recruiting young people hosted by a 16-year-old.

The consequences of involvement in these groups are devastating for both the child and potential victims. Most never take physical action, but the encouragement of violence by extremist “role-models” combined with “bomb-making and terror manuals […] lowers the hurdle for someone to take violent action” and plenty try to jump this hurdle. Arrest and conviction come with long-term consequences; 17-year-old Paul Dunleavy for instance was given a 5 ½ year prison term for his membership of FKD and terrorist activity.

Conclusion: how can young people be protected?

The UK Government provides “resources and direct support” to schools to help tackle RWE and counterterrorism officials are taking the threat seriously. From April 2020 MI5 took control of investigations into right-wing extremist activity, resulting in more convictions. Nevertheless, the convictions of child terrorists have not deterred others and while de-radicalisation programmes provided through Prevent or Channel are important, they start on the backfoot as the individuals they deal with have already exhibited signs of extremism.

Alternatively, Miller-Idriss puts forward a “pre-prevention approach”, which aims to stop individuals from entering “radicalisation pathways to begin with”, intervening when they are first exposed to extremism by developing “tools” to help care providers recognise early “warning signs” and explain the dangers of RWE. Child radicalisation, similar to other forms of child exploitation, drives a “wedge between young people and the adults they would normally trust.” Parents and caregivers need to feel empowered to speak to children about RWE; and above all, to be confident in challenging it. There are organisations Exit UK who work alongside communities to increase resilience and confidence in addressing extremism at its source.

Worryingly, the statistics at the start of this article were registered before COVID-19, which experts predict is likely to cause a further increase in online radicalisation. During long periods of unsupervised lockdown, children worldwide are spending more time online; a recent US survey showed a 500% increase in internet usage by children. This will inevitably lead to some children becoming more vulnerable to online radicalisation. Increased online extremism and COVID-19 has created what Neil Basu calls a “perfect storm” for radicalisation. To avoid being caught up in this storm authorities must provide extra resources to build resilience in countering right-wing extremism.

Thanks for reading our article! We know young people’s opinions matter and really appreciate everyone who reads us.

Give us a follow on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook to stay up to date with what young people think.