Can international solidarity defeat heated social media debates?

“The watermelon people picked the wrong folks to fight with. This will not end well for them”. Not long ago, if I was asked to guess what the identity was of the person saying those words, black American would not have been my first answer. But this statement - which feels deliberately mocking, condescending and offensive to say the least - represents an increasingly vocal view online from some black people, expressing that their support for Palestine conflicts with their own survival as black Americans.

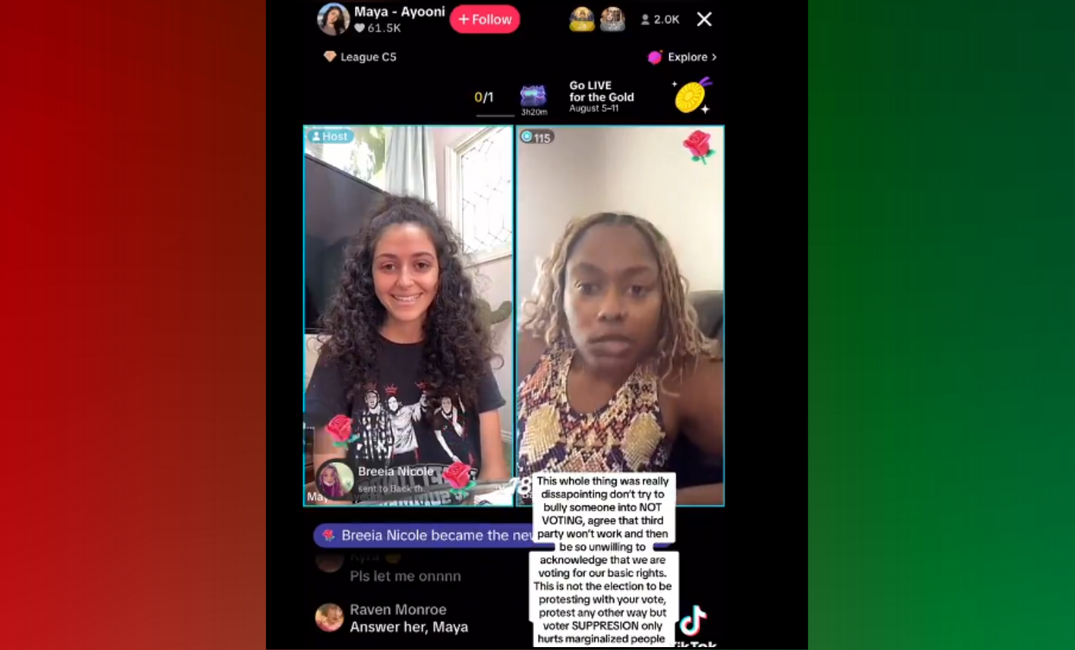

The incendiary comment followed an explosive TikTok “beef” between black American creator Tori Grier (who said she would no longer support Palestinians after being questioned on why she was endorsing Kamala Harris for President) and Palestinian creator Maya Abdallah. After asking Grier to “relax” during their heated debate, Maya was accused by some black users of “tone policing”, being a “Karen” and being a “hyper privileged Palestinian”. Abdallah apologised for any offence caused, but the discourse around black American support for the Palestinian cause is still being questioned; often posed in opposition to black people doing supposedly “what’s best for themselves” by voting for the black female candidate on the ballot.

What may seem like an innocuous TikTok spat, reveals something much more important about the soul of black radical politics, and whether globally as black people, we are living up to the values of international solidarity that antiracist resistance demands of us. In the context of this US election and the ongoing violence in Gaza - which has made clear that colonial oppression continues to harm many- how can we ensure that we live out the values that promise freedom for us and others?

There’s of course a legitimate debate to be had about the utility of voting for the “lesser of two evils”. We could argue it’s a harm reduction strategy to vote for Kamala to prevent a Trump presidency, whilst continuing to put collective pressure on her to change US foreign policy. But with much of this discourse taking place online, the conversation has taken on a much more antagonistic flavour.

Social media has expedited the liberal capture of “identity politics”. Initially a radical idea created in the 1970s by black lesbian group The Combahee River Collective, its core focus was how people should transcend the narrow confines of identity (along the lines of for example race, gender or sexuality). This approach advocated for recognising we share a bigger common struggle, foundational to successful political movements seeking to tackle injustice.

Like many radical ideas, identity politics has morphed into something quite different. Now it’s become about narrowing ourselves into smaller, more niche identity categories that are in opposition to one another. Being black becomes an identity reinforced as something real, rather than being recognised as a category made up by powerful people, for the benefit of powerful people. One particularly odd brain rot manifestation of this has been the insistence that solidarity with other groups must be “earned” like a transaction, rather than given because it’s the right thing to do. People who do not fit within the bounds of your identity become your adversary, someone you are against or in competition with, rather than someone who you have shared interests with.

Social media has failed to provide a strong educational base for anyone to engage well with this radical history or build wider communities, whilst enabling an expansion in access to information. The concepts that often prove most popular online are the ones that generate polarising opinions that divide people, rather than views that can bring us together. On the timeline, emotional outrage is currency. When activism is rewarded through engagement you have little incentive to build bridges, and far more to burn them.

Writer James Baldwin - who would probably be hailed a hero by many making these hollow identity based arguments- was actually quite critical about the limitations of these prescribed identities that have been given to us by racism. “Those categories which were meant to define and control the world for us have boomeranged us into chaos; in which limbo we whirl, clutching the straws of our definitions.” In a prescient quote from 1971 he said “people invent categories to feel safe”. These categories if we cling to them too hard, can start to hinder us.

As reflected in the TikTok creator clash, language used as an identity politics wedge almost always sounds startlingly similar. Palestinans are impulsively labelled as “privileged” in comparison to black people. Challenges to unquestioningly voting for Harris result in accusations of being a “Karen” or “centering themselves”. It strikes me as odd to use these terms in a context in which many Palestinians are watching their people being murdered and their ancestral homes destroyed.

Black people often feel as though they are at the bottom of the racial hierarchy, and a lot of the time this is true. Certainly in the context of the US, black people historically and currently often suffer the worst when it comes to areas such as housing, employment and healthcare. But an insistence that in any and every context black people are always ripe to be suffering the most, misses how malleable to change racial hierarchies are, and that blackness is subject to exploitation and weaponisation, like any other identity.

As black people we carry a lot of trauma for the past and continuing injustices levelled at us. I can understand why black people can feel sensitive to their own needs, it is a matter of survival that runs deep in our history. But I’m concerned that black people in the Global North may end up allowing our own trauma to undo the possibility for something truly liberatory, and it become weaponised as a way to oppress others.

Arguing that you need to worry about black people in the US before you worry about foreign policy also misses just how intertwined all of this suffering is. It isn't separate systems oppressing us - the US imperial war machine that funds the suffering of Palestinians in Gaza or The West Bank is the same system that devalues black lives globally. This was recognised by The Black Panther party in 1970, and West African leaders in 1973 who successfully pushed for the UN to acknowledge that Zionism was racism.

These nuances can make building solidarity harder. A news report published shortly after the bombing in Lebanon revealed that African migrant workers were being encouraged to stay in their workplaces whilst bombs were falling. This reminded me of the anti-blackness African migrants in Ukraine faced when Russia began its military invasion.

Whatever the complications, calling legitimate challenges from Palestinians racist, strikes me as a devaluation of anti-blackness, which is likely to impoverish people’s capacity to take anti-blackness seriously. It feels like we’re witnessing potentially the death of black radical politics and subsequently what writer Ta-Nehsi Coates - who has recently written about the violence unfolding in Gaza - called “the existential death of black people”. However, I remain hopeful that the disappointing social media discourse doesn’t necessarily represent most black people, neither in the US nor globally. Black people and Palestinians have long seen one another in our own oppressions. I hope we can keep that tradition alive for as long as we are facing injustice.

Thanks for reading our article! We know young people’s opinions matter and really appreciate everyone who reads us.

Give us a follow on Instagram and TikTok to stay up to date with what young people think.