Gerry Hart

Naked Politics Blogger

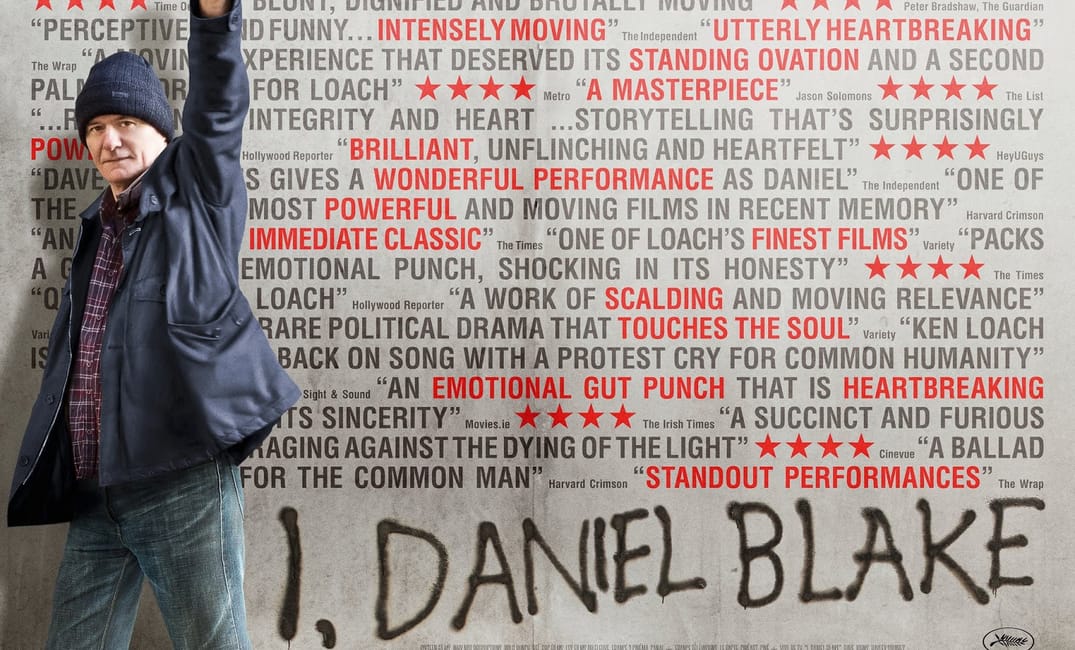

When it comes to cultural critiques of contemporary Britain, few are as widely known or as scathing as Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake. Ever since its debut at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival, the Palme D’or winning film has been inundated with praise from viewers, critics and politicians alike. With discussion recently reignited by its airing on BBC 2 earlier this month, it is only apt to examine the film’s impact more than two years later.

Set in Newcastle, I, Daniel Blake charts the misfortunes of the titular protagonist, 59 year old retired carpenter Daniel Blake (played by Dave Johns). In spite of his ill health following a heart attack, Daniel is deemed fit for work when applying for benefits, thus forcing him to find work he isn’t capable of doing. While attempting to navigate the hostile and bewildering benefits system, he befriends single mother of two Katie Morgan (played by Hayley Squires) who has recently been moved to Newcastle from London. For my part, I thought the film was excellent. It’s a tragic, emotionally charged tale of disempowerment and injustice mercifully interspersed with some much-needed moments of levity and humanity. Plus as a native of the northeast who lived in Newcastle at the time, its was rather affirming to see the city on the big screen, resplendent in all its concrete glory.

But I, Daniel Blake wasn’t created simply for the viewing pleasure of movie goers. A pioneer of the social realism genre, Loach postponed his retirement from filmmaking in order to create I, Daniel Blake with the explicit attention of drawing attention to the plight of welfare claimants in the UK. Indeed many of the major plot points drawing on the testimony of benefit claimants. For example the opening of the film where Daniel undergoes a work capability assessment before being rejected in spite of his doctor’s advice is clearly inspired by the numerous accounts of claimants’ experiences of such assessments. These accounts typically paint a uniformly bleak picture characterised by shocking incompetence and almost intentional humiliation as demonstrated by testimony given to the Commons Select Committee on Work and Pensions detailing, among other examples, suicidal claimants were asked why they hadn’t taken their own life.

One might argue that a fictionalised representation of the benefits system is redundant given the plethora of criticism levelled against it. In October 2016 the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities published a report accusing the UK of “grave and systemic” violations of the rights of disabled people. Other critics have noted the numerous deaths linked to current welfare policy such as Mark Wood, a 44 year old man with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Asperger Syndrome, who died at his home in Oxfordshire, severely malnourished, after being assessed as fit for work. But what I, Daniel Blake does is weave an engaging narrative from the lived experiences of thousands of welfare claimants to appeal to the viewer’s sense of empathy in a manner that dry reports could not. It is, in brief, a call to action. As Loach stated regarding the film’s intentions, “I suppose why you hope (I, Daniel Blake) connects to people is that we need to fight back.”

So if I, Daniel Blake was intended to affect change in policy, did it succeed? Well…no, though there have been some changes via the roll-out of Universal Credit that’s hardly a change in direction that we need. Announced in 2010, Universal Credit constitutes an attempt to streamline the benefits system by rolling a number of previous benefits into one singular payment. Seems fairly sensible, right? Unfortunately, Universal Credit has been accused of being even more degrading than the previous system. Newcastle, the city chosen to trial Universal Credit (because god forbid the Tories test their precious scheme in their own backyard) reported delays in payments putting claimants at risk of homelessness, with council leader Nick Forbes warning Universal Credit would be a disaster if it were rolled out nationwide. Another report published by the aforementioned Work and Pensions Committee has also alleged that Universal Credit could be used by domestic abusers to financially control their victims by not splitting payments between household members.

And yet when presented with criticisms like these, the government’s response is to essentially ignore them. As one particularly scathing UN report noted, when pressed ministers would, among other equivocations, “blame political opponents for wanting to sabotage their work”. This dismissive attitude has also been extended to I, Daniel Blake. When Shadow Business Secretary Rebecca Long-Bailey recommended watching the recent BBC 2 airing on Twitter, Conservative Party Chairman James Cleverly replied “You do realise that it’s not a documentary, don’t you. Don’t you?” (which is either indicative of Cleverly’s poor understanding of fiction as a vehicle for social commentary or his unwillingness to listen to the film’s core message). The DWP has additionally been accused of adopting a “fortress mentality” when it comes to their welfare reforms, even ignoring the advice of senior civil servants. This isn’t policy founded on economic practicalities or a sense of equity. These reforms are an ideological project founded on a Victorian conceptualisation of poverty and contempt for those caught in its grasp and ministers aren’t budging.

Does that mean that I, Daniel Blake was a failed endeavour? Not entirely. True it didn’t bring about any change in government policy but I would argue it found success in another capacity. By utilising the medium of film, I, Daniel Blake works humanises a group of people often maligned as feckless scroungers by unsympathetic politicians and media outlets and thereby provide a counter narrative to use against rhetoric such as this. If just one person came away from the film with a little more empathy for welfare claimants, that alone is a victory. But a counter narrative is not enough. If I, Daniel Blake demonstrates anything it is that art, no matter how moving, cannot in isolation bring about tangible political change if the objects of its criticism are unwilling to acknowledge its message.