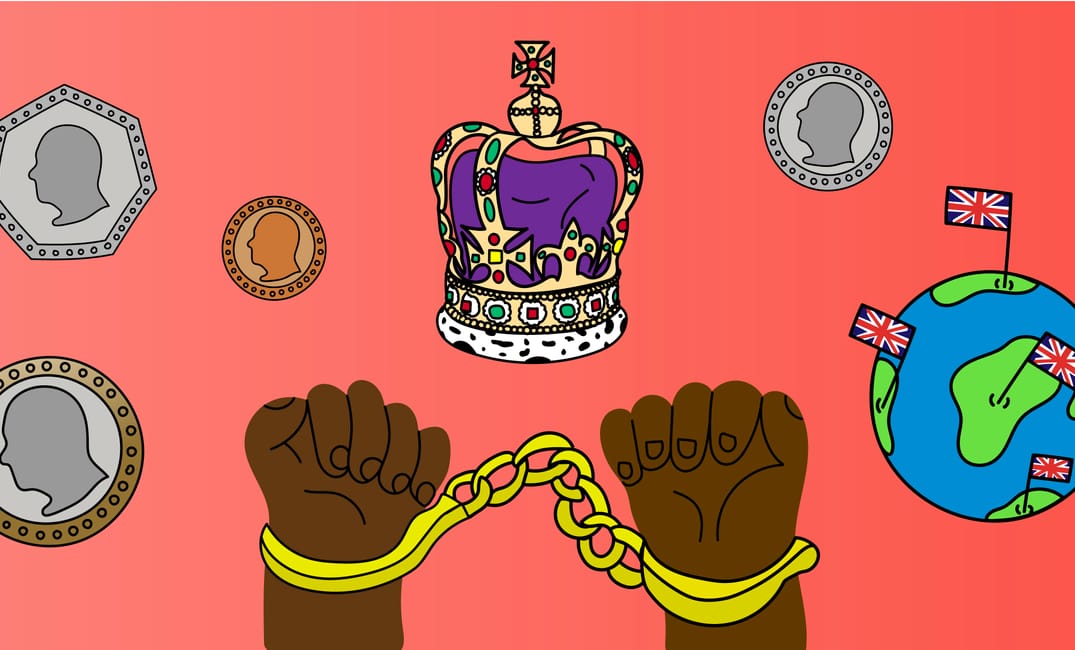

Text by Banseka Kayembe / Illustration by Rhia Thomas

For a long time, race and monarchy were rarely mentioned together in mainstream British public discourse. The British monarchy managed to sit above most politics, buttressed by a press that seemed invested in largely positive coverage of Queen Elizabeth, or viewing the royals through the lens of celebrity gossip and interpersonal turmoil. Any explicit racism (often from Prince Phillip) tended to be framed fondly as “gaffes”, mere slip ups rather than anything more insidious. The elephant in the room, both in who was capable of being constituted as “royal” and the source of their wealth was never addressed.

2020 brought about somewhat of a paradigm shift, at least on a superficial level. The violent murder of Black American George Floyd compounded by a global standstill courtesy of Covid led to some unavoidable questions of some of our oldest institutions; the long rumoured old royal adage of “never complain, never explain” wore a bit thin. Further allegations were made by Prince Harry and his biracial wife Meghan that concerns were voiced about how dark their unborn child’s skin colour would be, and that Meghan was given no protection from the onslaught of racist press coverage.

This was an unprecedented step in questioning the values of the institution. Further stories broke, such as The Queen for a period of time having a household ban on hiring staff of colour. It was alleged her long-time lady in waiting Lady Susan Hussey felt comfortable enough within the confines of Buckingham Palace to repeatedly ask the Black charity CEO Ngozi Fulani where she was really from.

Support us!

Support us by contributing as little as £1 so we can continue to give young people a voice and a platform they deserve.

£1.00

But these interpersonal allegations are just the tip of the iceberg. The British monarchy has a long history intertwined with the exploitation of those racialised as non-white, for their own financial benefit. So what is this history and how does it inform the way the monarchy operates today? With considerations about race now seeming unavoidable, how might the monarchy adapt, and will it really be any different?

The slave trade

Initially dominated by the Portuguese, Spanish and to a lesser extent the Dutch, Britain’s first major endeavours into the slave trade was supported financially by Elizabeth I in the late 1500s. Sir John Hawkins kidnapped Africans and transported them to Spanish plantations in the Americas, setting the pattern that became known as the English slave trade triangle. Elizabeth I sponsored his subsequent journeys and provided ships, supplies and guns. She also gave him a unique coat of arms bearing a bound slave. Monarchy and private enterprise would continue to have a long-standing relationship, at the exploitation of millions.

Post the English civil war and fall of Oliver Cromwell, the monarchy was reinstated, but with the petrifying reality that monarchs could actually be deposed. Charles II becomes seriously committed to involving the crown in the slave trade, pivoting away from sourcing gold and enslaving Black Africans instead, to be less financially dependent on the revenue streams they had within the UK. The Royal African company was born, with the financial investment of other royals including James I (then the Duke of York) as the largest shareholder, the Queen mother, Princess Henrietta and Prince Rupert of The Rhine. Charles II also married a Portuguese princess in 1662 as a strategic economic and political alliance; to get into Portuguese territories and further into the slave trade. Investment in capturing land in the Caribbean for slaves to live and work on expanded their portfolio.

Author of “What White People Can Do Next” and Academic Emma Dabiri told Channel 4 that the royal involvement in slavery helps start “setting the wheels in motion for the invention of race”. The justification for slavery, and ensuring poor labourers of all colours were divided was underpinned by the invention of racial categories, and as a result the racial hierarchy we still live under today. Monarchy itself always is based on some sort of “blood purity” ideal, the concept that some are born to rule. The intermingling of class purity, with racial purity cannot be separated.

In the 1680s approximately 100,000 people were enslaved and brought to the colonies, though many did not survive the journey due to brutal conditions onboard. It was certainly not small in scale; by 1687 tax revenue of customs on colonial goods produced by slave labour was one third of total crown revenue. Enslaved Africans are branded with RAC, or sometimes with the initials of individual royals (DY for the Duke of York). This demonstrates that the royals were not involved passively, but were direct owners and profiteers of people they viewed as their chattel.

The royal involvement continued into the 17th and 18th centuries. Queen Anne won a contract allowing the English to transfer enslaved Africans to Spanish America in 1713, later selling the contract to the South Sea Company for £17 million. The Queen enjoyed a quarter of the profits generated from the slave trade, worth £200 million in today’s money. George I then inherited her shares and purchased more, becoming an honorary governor of the South Sea Company.

The rebellions

In many of the colonies, enslaved people made up the majority of the population, making the capacity for resisting enslavement and overthrowing British rule possible. Tacky’s Revolt in Jamaica (1760-1761) is considered one of the most important collective acts of resistance to British rule. Many enslaved Africans in this revolt were thought to have military expertise, to the bafflement of the British establishment who were shocked at their ability to organise. There were also revolts in Demerara in 1823.

Historian Brooke Newman told the podcast Human Resources “if it’s not for resistance, and for the actions of enslaved people themselves…the abolition movement would not have been as successful, and that emancipation would not have been granted during the 1830s. It’s far worse…from the Crown’s perspective, to lose these colonies completely than it is to contemplate winding down reliance upon the transatlantic slave trade, which has, over time lost favour among the British public because of the abolitionists campaign”.

End of the slave trade and continuation of colonialism

There are some who might prefer to emphasise the role the royals took in the ending of the slave trade- but there’s a lot of evidence suggesting they didn’t really embrace abolition until the public pressure to unwind the brutal trade was very substantial. George III shared some private misgivings about the morality of slavery, but defended it for most of his long reign publically. His son Prince William gave a pro-slavery speech in the House of Lords. Apart from the Duke of Gloucester (George III’s nephew) the whole Royal Family opposed abolishing the slave trade until the end.

Newman emphasises the royal family still didn’t “officially embrace anti slavery in any meaningful way until 1840” at London’s first anti-slavery convention, after three hundred years of profiteering directly from enslaved labour. The abolition of slavery comes with compensation of slave owners for loss of their profits (which British taxpayers were still paying off until 2015) not the enslaved people themselves. They are freed, but given no land, financial reparations and continue to be oppressed politically, socially and economically by the white elites still dominating these territories.

Chinese and Indian people began replacing the enslaved Africans, as a form of contractual labour. However the working conditions were reportedly brutal, and workers were misled as to what they were owed upon arrival in the colonies. The crown jewels today contain the Koh-Ni Diamond, an extremely valuable jewel taken by the East India Company. Closer to home in countries like Ireland – which is often described as “Britain’s first colony”- the justification for colonisation was underpinned by racialising the Irish as distinct from whiteness. It was a “laboratory both for imperial rule and for resistance to that rule”.

Modern day

History shows us that, far from a benign involvement in slavery and colonialism, the British monarchy have been key players in a violent global system that continues to shape millions of people’s lives today. They may not hold any hard power anymore, but they continue to hold the immense wealth gained and we still live in a globalised capitalist economic system pioneered by them that keeps wealth in the pockets of the few over the many.

Fast forward to the mid 20th century and Queen’s record on race was in many ways fairly poor. She never sought to engage in any public discourse about racism, and even small wins like changing the names of some honours to not include explicit reference to the British Empire she refused. But, with more precarious popularity rates, and a more liberal outlook, King Charles’ attitude does seem somewhat different. Last year, he apologised for slavery, and he guest edited “The Voice” Britain’s only Black newspaper and has signalled explicit support for research into the monarchy’s links to slavery. All this appears to be a step in the right direction.

But, as explored in this article, much of the history around slavery is already known, and framing it as “links” already understates how integral to their private wealth slavery has been to generations of royals. It’s a tactic that has been used by other institutions, such as Bristol University, The Bank of England and The Guardian newspaper, to undertake research as a form of atonement for past wrongs, whilst still enjoying the ill-gotten wealth in the present. Companies “going woke” works wonders for their reputations and their bottom line, making this research seem like a superficial attempt to seem anti-racist, whilst never actually atoning for the fundamental economic exploitation through reparations to those communities wronged.

Even Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, now somewhat outsiders to the institution and hailed by some as more modern royals, appear to have a very superficial understanding of racism. Prince Harry framed allegations made that appear to be very explicitly racist, as “unconscious bias” a conspicuously euphemistic term that suggests there is a lack of awareness from those perpetrating it. Harry and Meghan’s “activism” feels bitesize and instagrammable, often lacking substance. Harry’s anti-racism doesn’t appear to extend to his understanding of modern British imperialism. Their main gripe seems to be having not been able to personally enjoy the spoils of monarchy, rather than questioning the very existence of the institution itself.

It seems clear that decolonising the monarchy, a system where inequality is inherent to how it functions cannot ever be possible, despite the PR and marketing King Charles will no doubt spearhead in a bid to keep the institution palatable for the next generation. As younger people continue to question its legitimacy more, we could be on the brink of a future without a monarchy; but you can be certain the change needed won’t be coming from the institution itself.

Thanks for reading our article! We know young people’s opinions matter and really appreciate everyone who reads us.

Give us a follow on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook to stay up to date with what young people think.