By Tiernan Cannon

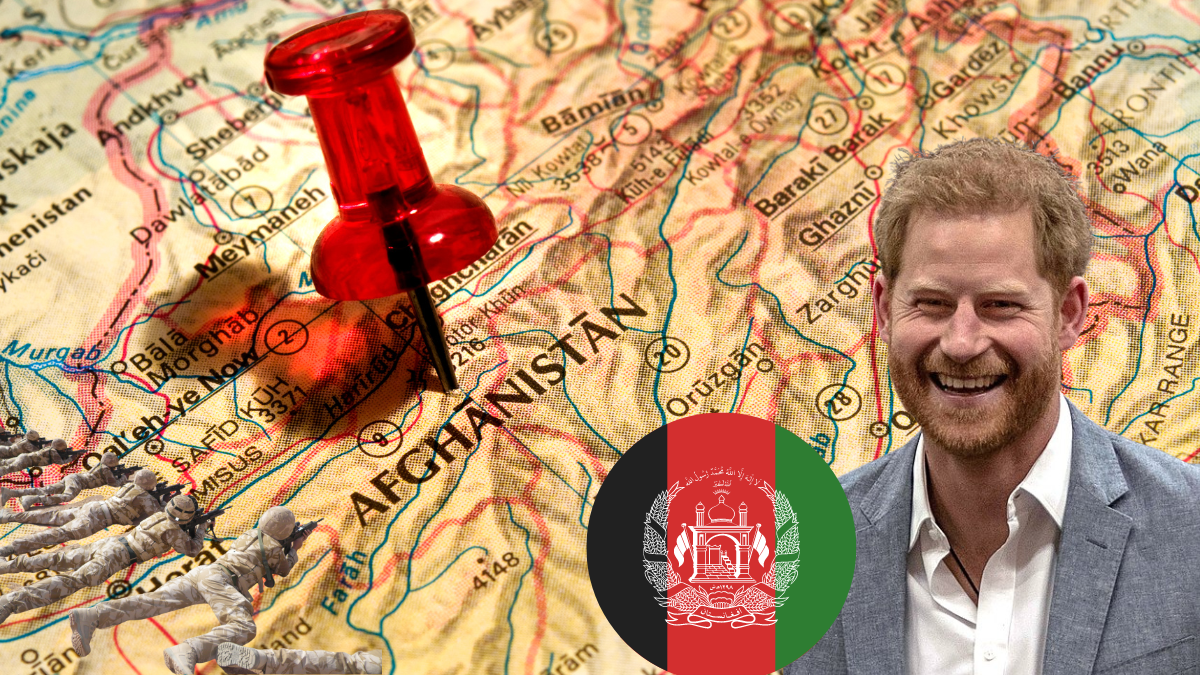

Prince Harry is not ashamed. He killed 25 human beings while serving in Afghanistan. It is not a number that fills him with satisfaction, nor is it one that embarrasses him. Twenty-five is his number.

“While in the heat and fog of combat,” Harry has written in his memoir Spare, “I didn’t think of those twenty-five as people. You can’t kill people if you think of them as people. You can’t really harm people if you think of them as people. They were chess pieces removed from the board, Bads taken away before they could kill Goods.

“I’d been trained to ‘other-ize’ them, trained well.”

Support us!

Support us by contributing as little as £1 so we can continue to give young people a voice and a platform they deserve

£1.00

There are clearly more urgent concerns facing Britain today than the woes of a rogue, rosy-cheeked prince, but it’s worth lingering on these particular remarks for a moment. His words, and, more pertinently, the general response to them, reveal a lot about Britain and its elites.

The British press has been highly critical of the prince’s admission. Adopting a tone of abject horror at his apparent callousness, it has exhibited its dismay by quoting several prominent figures from the British military.

“He has badly let the side down,” the widely cited retired colonel Tim Collins has lamented. “We don’t do notches on the rifle butt. We never did.”

Former British Army colonel Richard Kemp, meanwhile, suggested to The Telegraph that Harry’s “badly judged” comments might pose a genuine threat to the United Kingdom.

“These comments feed into propaganda and help the jihadists to recruit and radicalise people to carry out attacks against British civilians and soldiers,” the former colonel said, seemingly unaware of the possibility that, perhaps, an illegal invasion of their country might itself have effectively propagandised many Afghans into considering violent retaliations against the enemy.

It doesn’t take a terrific amount of scrutiny to sense the tone underlying these responses. It is one of mere distaste rather than horror. The statements hum with the suggestion that, ultimately, it just wasn’t very sporting of Harry to imply the British military doesn’t have the utmost respect for the people it slaughters.

Figures like Collins and Kemp and, indeed, like Tony Blair, look down upon the people of Afghanistan with a cruel indifference, just as Harry did from the safety of his Apache helicopter. They pretend to care about them as a way to justify their crimes, forever offering hollow rationales for their war-making. That they sought to bring democracy to a barbaric and wild land. That they sought to save women and girls from the oppression of the Taliban. The fact we are two decades on now and the Taliban are back in power, Afghan women are suffering terribly under their rule, and unspeakable numbers of people are needlessly dead seems not to be cause for much self-reflection within Britain’s upper echelons.

The truth, of course, is that neither Britain’s aims nor its conduct in Afghanistan were noble. Nowhere is that more apparent than in a BBC report published in July 2022, which claims SAS operatives in Afghanistan “repeatedly killed detainees and unarmed men in suspicious circumstances.” As many as 54 people may have been unlawfully killed throughout the course of a single six-month tour, the report alleges, with high-ranking officers potentially aware of the murders and attempting to cover them up.

The details are grizzly. The report states, “Several people who served with special forces said that SAS squadrons were competing with each other to get the most kills, and that the squadron scrutinised by the BBC was trying to achieve a higher body count than the one it had replaced.” So much for Colonel Collins’ assurances that British forces “don’t do notches on the rifle butt” – a claim, incidentally, that did not appear to meet terribly much resistance in the outlets quoting it.

The prospect of justice ever being done for any of the alleged war crimes committed by Brits in Afghanistan is, of course, unlikely. The military and the government have both worked hard to make sure of that.

In 2014 the Royal Military Police launched an investigation known as Operation Northmoor, which looked into more than 600 alleged offences committed by British forces in Afghanistan. By the time Operation Northmoor closed five years later, not a single prosecution had resulted.

According to the BBC report, members of Operation Northmoor’s investigating team dispute its findings on the grounds that they were obstructed by the military from gathering evidence. The non-profit Action on Armed Violence, meanwhile, has pointed towards “serious weaknesses” in the investigation, stating that only a handful of the incidents alleged to have occurred were ever examined in detail.

British lawmakers have also done their part to keep a lid on what their forces get up to in faraway places. In 2020 the Overseas Operations (Service Personnel and Veterans) Bill was introduced to provide serving and former military personnel with “more legal protection from prosecution for alleged historical offences resulting from overseas operations.” In plainer terms, the bill sought to reduce the possibility that any British person will ever see justice for committing a war crime. It became law in 2021.

We see very clearly the lengths Britain’s leaders will go to in order to ensure the public does not think too carefully about the atrocities committed in its name. That is why we see such a fevered response to Harry publicly discussing his kill count.

The prince’s great sin is not that he killed so many people during the course of his duty in Afghanistan, but rather that he has drawn attention to the great evil done there. He has revealed the truth that, to our leaders, the Afghan people are not quite human. They are just chess pieces to be removed from the board.

Thanks for reading our article! We know young people’s opinions matter and really appreciate everyone who reads us.

Give us a follow on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook to stay up to date with what young people think.